Last Updated on 12 November 2017 by Eric Bretscher

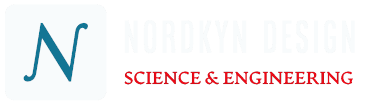

Yacht building costs break-down in material costs, labour and some ancillary costs that don’t contribute to the final product, but can’t be eliminated either, like leasing space or equipment.

There are different ways of undertaking the construction of a yacht, but the basic cost components remain the same, the difference is the extent to which they apply

The proportions shown above vary widely. Labour costs are very location-dependent and can easily exceed material costs; those however tend to remain comparable everywhere. In New Zealand, for example, for a long time labour remained surprisingly affordable for a fully-developed country, quality is high and equipment availability is very good, hence the number of superyachts built for overseas interests. It is not as attractive any more now and there is too little competition for building mid-range yachts. In order to be competitive, a yard generally needs to have its own marine engineers, electricians, riggers etc, or all these services are going to come at a very high added cost.

Ancillary costs are all additional expenses in the build that do not directly result in physical, tangible outcomes.

Direct Material Costs

Material costs include all supplies, raw materials, consumables and equipment required to complete the vessel at the cost of sourcing them.

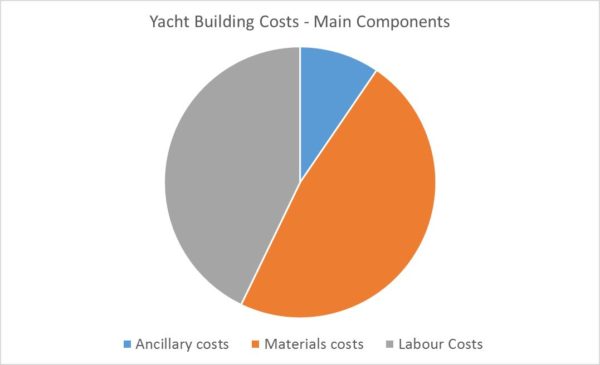

Some broad, but useful relations exist between the different fractions of the material costs; a typical one is the cost of the shell materials versus the total in materials and equipment.

The breakdown below was extracted from my records from building the 13-metre aluminium sloop Nordkyn. It should be relevant for similar projects that include high standards of quality and finishing, great simplicity and a rigorous sourcing strategy.

The percentages listed are fractions of the total material cost as sourced, not total vessel cost, unless no other costs (such as labour) are incurred:

| Rigging. This includes all spars, including spinnaker pole and all standing rigging, but not running rigging or sails, which are included under Equipment, and no furling gear. |

18% |

| Alloy shell and appendages. This includes the complete hull, deck keel and rudder. Appendages themselves accounted for 3% of the total. |

16% |

| Equipment. This is all “mobile” sailing gear, including a full set of sails, ground tackle, safety equipment with the exception of liferaft, EPIRB and flares that have a shelf life. |

13% |

| Deck hardware. This covers all deck-mounted hardware, hatches, windows, winches, blocks, tracks, travellers etc, but no steering vane. |

12% |

| Coatings. All paints (inside and outside) and all fairing products used outside the hull. |

11% |

| Interior. All interior materials and fittings, including fairing where relevant, but excluding lighting, which is included under Electrical. |

10% |

| Powering. Engine, transmission, shaft, propeller and all associated material costs. |

9% |

| Instrumentation. Electronic and VHF/SSB radio equipment. Basic instruments, no plotter, radar or electric pilot. |

3% |

| Electrical. All electrical costs, charging system, lighting, navigation lights, solar panels, batteries, wiring. |

3% |

| Cabin equipment. Stove, toilet, galley gear, heating, bedding, upholstery, etc. |

2% |

| Plumbing. Water, bilge, fuel and LPG plumbing. |

2% |

A few comments:

-

The rigging fraction is very high, but suppliers of rigs of the size required were few and global and, when building a one-off, leverage is lacking and internal engineering costs are being incurred. Buying the extrusions and building most everything else could have been cheaper, but inferior in quality and longevity.

Some (of the best) mast makers simply won’t sell their extrusions alone or sell partial solutions to protect their reputation.

The relative cost was also clearly influenced by the size of the rig in relation with the displacement of the vessel. -

Powering. A builder benefitting from trade volume would have had access to better engine pricing than I had, but the difference would likely not exceed two points.

- In spite of the foam core composite construction, the interior build only contributed to 10%.

- The coatings budget was very significant, the result of the finish quality sought, the aluminium substrate and a painted interior. Half of what was spent would likely represent the lower limit.

- You can literally spend as much as you want on instrumentation and electronics. The amount included here already covers items useful, but not necessary.

- The plumbing budget is clearly higher than usual as a result of the multiple watertight compartments and bilges, but also the use of stainless steel fuel lines etc.

- Plan printing and other small items fell into the residual 1% not accounted for.

If you are considering building a sailing yacht, the table above contains useful information.

At a glance, one can see that the cost of building the interior was 62% of the cost of the shell for example. Also, while building the hull is often perceived as a major cost and undertaking, it is anything but supported by the data. This is the prime reason for so many projects lying abandoned everywhere: if you suggest that the total materials bill will amount to over six times the value of those in the shell itself, people refuse to believe it.

The figure here relates to a high-end job, but even in the case of a rough build, materials for the completed vessel are still likely to cost at least 4 to 5 times the value of those in the shell.

Sailing yachts are expensive from the deck up, in miscellaneous hardware, sails and rigging: 43% of the total material cost here.

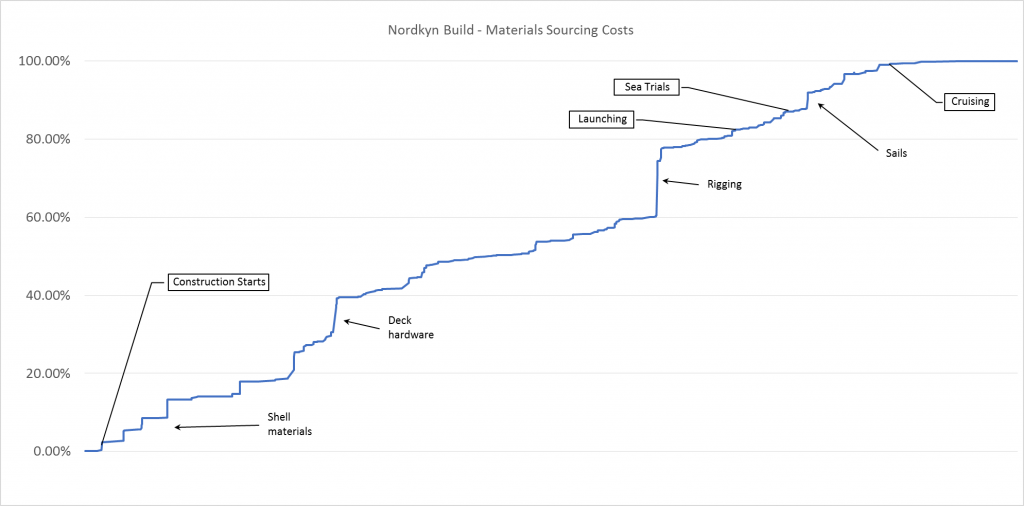

Another item of interest is the project cost curve. Here, we will inspect the materials cost curve alone, because labour costs are too location-dependent and would blur the picture.

Regardless of project duration, this curve should still look the same, so I removed date references along the bottom axis. Note the small stairway as the alloy shell was being fabricated at the beginning, materials were purchased in lots as needed. Some fairing and painting of the hull takes place with very little needed, until the hull is turned over. Then we see engine installation (a mistake, too early, it should have waited nearly as long as the rigging) and a steep rise as most of the deck hardware is being sourced to allow finishing the deck plane. A long light slope follows as the deck is completed and painted and all the interior is being built. Sourcing of the rig results in a big hit, but delivery issues delayed launching.

Sails waited until the mast was standing and then a lot of the costs came trough after they had been received. More sails followed as well as cabin and sailing gear.

This is a fairly healthy materials cost curve, because it tracked very tightly with construction progress.

Margin on Materials

Owner builders successfully cut this out only if they can access similar pricing structures available to commercial yards. This is not always the case. In the case of a personal project, it can be better to seek an agreement to source equipment through an established yard for example, rather than incur retail pricing.

The strategy is always the same:

- Try to consolidate supply

- Investigate options

- Negotiate pricing

If the build is going to be contracted to a yard, a margin will apply on materials. This is reasonable as there is a cost in organising the required equipment and most yards do not charge distinct project management costs.

Yards also expect to be left with a net profit from supplying materials. Marine construction is often a competitive market and yard owners are seeking additional revenue besides direct labour to “make a go” of it. They can get quite irritated when the client attempts to cut them out by supplying directly and sometimes inflate their labour to offset this.

A fair, up-front discussion and a transparent agreement on margins is often by far the best strategy for a contracted build.

Labour Costs

Labour is a very significant component in one-off marine construction and can easily compare or exceed material costs, so labour efficiency is critical. If you build your own boat, the whole idea is eliminating this cost altogether – and it works – but the challenge is then preserving efficiency. You may end up the only person on the job and it can be inefficient.

Labour efficiency is the relation between effort and result. It requires that workers know what to do, how to do it and are just enough to do it.

If you build your own yacht, you can usually afford some learning curve, provided the core skills exist, but you still need to know what to do and you may need an extra hand to help at times.

You will seldom get more than what you expect, but you will usually get what you are prepared to tolerate

In the case of a contracted build, there are five situations where labour costs get out of control very quickly:

- Indecision. The workforce is available and allocated to the project, but important, complex decisions constantly need to be made. As a result, everyone is standing around talking about the pros and cons instead of building the vessel. Such discussions often take place at a rate of hundreds of dollars per hour and in the meanwhile there is no progress.

Typically, the design data is insufficient or it is an alteration/refit job and there is no plan for it. A clear, detailed plan that removes decision processes from the construction floor is invaluable. It may look expensive up-front, but it will save you the extra cost many times over and the vessel will be available earlier.

Designers who sell a set of lines for a few hundred bucks don’t really want to be plagued with constant queries for months or years afterwards. Those who sell a fully detailed plan at a premium don’t face so many questions in the first place and don’t mind answering the ones they get. - Lack of project management. If the design information is good, but the job is still not tracking, it can come down to a lack of direction and leadership. If the yard doesn’t have the leadership capability, but the resources and construction skills are there and the rates are attractive, you may want to consider hiring a project manager. Typically, he/she will preside over sourcing, logistics, allocation of work and resources as well as quality management and keep the build on track. You need someone capable and knowledgeable in the field.

- Incompetence and/or lack of experience. Work with people who have done it before, or fully take into account the fact they haven’t in the cost structure. Ideally, one would want to say “don’t do it”, but it still happens all the time. People often try to work with people they already know and sometimes make wrong calls on this basis. Be prepared to wait for delivery and be prepared to have to seek and inject external expertise if it happens.

If this is not enough, take the project elsewhere at the first opportunity. - Under-resourced. Is the outfit big enough to tackle the project? Is the workforce sufficient? What fraction of their workforce can they dedicate to the project? Can they tap into additional resources if needed?

One person trying to do a two-man job single-handedly won’t take twice the time. It will take a lot longer than that, because typically the job requires more than two hands, or requires to be in more than one place at the same time to be done efficiently. Look at the make-up of the workload in the business. Routine, steadily reoccurring work for established clients will always take precedence over a project if there is competition for resources, because on the long run it makes more money and represents a secure income for the company.

If this can’t be resolved, take the project elsewhere at the first opportunity. - Over-resourced. There are only so many tasks that can effectively be progressed in parallel and one can only make use of so many hands to complete a task. Efficiency drops very quickly if unnecessary resources are allocated to the job.

This happens readily when larger firms need to keep their workforce occupied. Employing an independent project manager on a build can be the best way of controlling costs; the project manager is an independent third party working with everyone on behalf of the owner, and with the interests of the owner at the forefront.

If you are facing such issues and you have a good grasp of the work being done, walk on the job first thing in the morning, ask what the exact programme for the day is and look at who has been assigned to do it. If needed, make your expectations clear with the management and get the staff allocation reviewed. Excess resources will usually get transferred onto someone else’s job.

Come across as firm, but diplomatic, the blade can cut both ways. If you don’t get a review on that day, but it never happens again after, it is as good as a win.

This leaves the question of how much labour and how long it is going to take. Find those who know, ask them, compare the answers you get and work on understanding the differences. Alternatively, seek data from a similar project if you can.

Marine construction is another field where you don’t get something for nothing. If you are tempted by a lower price or estimate, ask yourself whether you are prepared to accept lower quality and/or specifications. Understand what you are leaving out.

Ancillary Costs

Design costs are incurred up-front before actual construction starts, but survey, compliance, certification, inspections, rental of premises, transportation, cranage, temporary berthing, fuel for trials (in the case of motor yachts) and more can all add significantly to the final bill outside of the original budget.

Was the agreed lump sum supposed to cover such and such cost?

In the case of a build contract, ensure that clarity exists regarding the scope of services and who pays for what, especially if a lump sum agreement is in place for the delivery of the vessel or part of it, otherwise the argument is almost guaranteed to spring up as none of the parties will be keen to pay for those.

The Value of Time

Time tends to cost on construction projects; faster is usually better up to the point where penalties are incurred for the rate of progress. Paying overtime rates is such an example that requires further justification.

If the project is going to take time, typically due to limited available resources, you need to specifically set up the project to control and eliminate as much as possible time-dependent costs

Why is faster better? Time-dependent costs, such as leased space for construction, accumulate until the vessel is out whether it is being worked on or not. Time-value of money is the other aspect often overlooked.

Money tied-up in a half-built vessel lying around earns interests for those who received it, not for the owner who paid it. For the same completion date, it would have been wiser to defer the start and keep the capital longer. On large projects, this becomes very significant, but even on a personal build, the difference can easily amount to thousands of dollars.

Cash flow – Learn from Industry Best Practices: Just-In-Time

Don’t source equipment before you actually need it for a reason on the job, unless there is a very clear and undeniable benefit in doing so, like a clearance price that won’t be available again or quantity-based rebates. Even then, try to agree on the discount rate based on a commitment to purchase the balance later.

Never, ever, buy electronics, instrumentation or computer-type equipment until the project is near-complete. Performance and features keep improving, price usually drops over time and warranty periods are short.

New engines are pre-lubricated from their last run at the factory and have a shelf life of some 3 years or so. Check before you buy. Once shelf life expires, obtaining a warranty on them can be near-impossible due to the risk of severe damage at start-up. Some dealers may use the necessary precautions and still stand behind the product, but many will simply walk away in case it has been cranked already and the bearing shells are damaged.

I have seen many private boatbuilding projects where huge amounts of equipment had been purchased, but little work had ever been done. In the end, the brand new gear is obsolete before it has even seen the light of day – if it ever does. It is senseless. This is just buying a false sense of progress and achievement.

Whether you build yourself or contract the project out, keep your capital for as long as you can and progress the job as fast as you realistically can. And don’t stop until finished.

Marine construction yards love milestone payments, the more up-front the better. Contractually establishing a progressive payment schedule that tracks the effective cost of the build is the first step towards controlling cash flow and reducing financial risks. The last thing you want is your milestone payment to be absorbed to progress another job.

Hi Eric,

Was the ‘premature’ installation of Nordkyn’s engine a deliberate decision to ignore the ‘Just-In-Time’ principle in favour of other considerations? If so, what were they?

Thanks – Peter

Peter,

There were no other considerations than a degree of convenience, but the drawback of ending up with no warranty was never perceived or anticipated either at the time. In the end, it never made any difference: the engine has a little more than 100 hours on the clock now, but it also took over 5 years to get there. In this context, you can see that the “1 year from start up or first 100 hours, whichever comes first” warranty statement is in fact of very little value… in my case, such a warranty is bound to expire before I get any chance to test it.

The net effect here was that it turned out to my advantage:

1/ I saved paying the agent for coming down, inspecting the setup and starting up the engine for the first time, as he didn’t want to know about it any more and this represented a lot more than the value of deferring the purchase by say 3 years.

2/ I was able to start up my engine myself, and I did so with a lot more care than what agents often take. When you have to do those things all the time, it is easy to get a little too casual with them.

Having the engine available early was convenient in terms of lining it up and adjusting the shimming and the exact space available in front of it. Today, things are somewhat nicer because you can get 3D CAD engine models from the manufacturers and literally install the engine into the drawing with every detail included. This is what I always do these days, but, at the time, I had to work with a profile only.

Hindsight is also a wonderful thing and today I would most certainly buy it almost at the last minute only, after having completed everything outside and all of the interior construction as well.

Regards,

Eric